Surgical treatment for gum disease, also known as periodontal surgery, becomes necessary when non-surgical interventions like deep cleaning (scaling and root planing) and improved oral hygiene fail to control the progression of the disease. Advanced stages of periodontitis, characterized by deep periodontal pockets, significant bone loss, and persistent infection, often require surgical intervention to access and clean affected areas thoroughly. Procedures such as flap surgery, bone grafting, and tissue regeneration aim to reduce pocket depth, repair damaged bone, and promote gum reattachment to teeth. Surgical treatment is also considered when gum disease has led to severe complications, such as tooth mobility or abscesses, or when cosmetic concerns like gum recession need to be addressed. A periodontist typically evaluates the extent of the disease through clinical exams, X-rays, and pocket measurements to determine if surgery is the most effective course of action.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Severe Periodontitis | Surgical treatment is required when gum disease progresses to advanced stages with deep periodontal pockets (>6mm) and significant bone loss. |

| Non-Responsive to Non-Surgical Therapy | When scaling and root planing (deep cleaning) and antibiotic therapy fail to control infection and reduce pocket depth. |

| Recurrent Infections | Persistent or recurrent gum infections despite repeated non-surgical interventions. |

| Bone and Tissue Regeneration Needed | Surgical intervention is necessary to regenerate lost bone and gum tissue, often using bone grafts, tissue grafts, or guided tissue regeneration. |

| Access to Deep Root Surfaces | Surgery is required to access and clean deep root surfaces that cannot be reached with non-surgical methods. |

| Correcting Gum Recession | Surgical treatment is needed to address severe gum recession that exposes tooth roots and causes sensitivity or aesthetic concerns. |

| Furcation Involvements | When the disease affects the furcation areas (where tooth roots meet), making non-surgical treatment ineffective. |

| Aesthetic and Functional Restoration | Surgery may be required to improve gum appearance, restore proper tooth function, and prevent tooth loss. |

| Persistent Bleeding and Swelling | Chronic bleeding, swelling, or pus discharge from gums that does not resolve with non-surgical care. |

| Systemic Health Impact | Surgical intervention may be necessary if gum disease is contributing to systemic health issues like diabetes, heart disease, or pregnancy complications. |

What You'll Learn

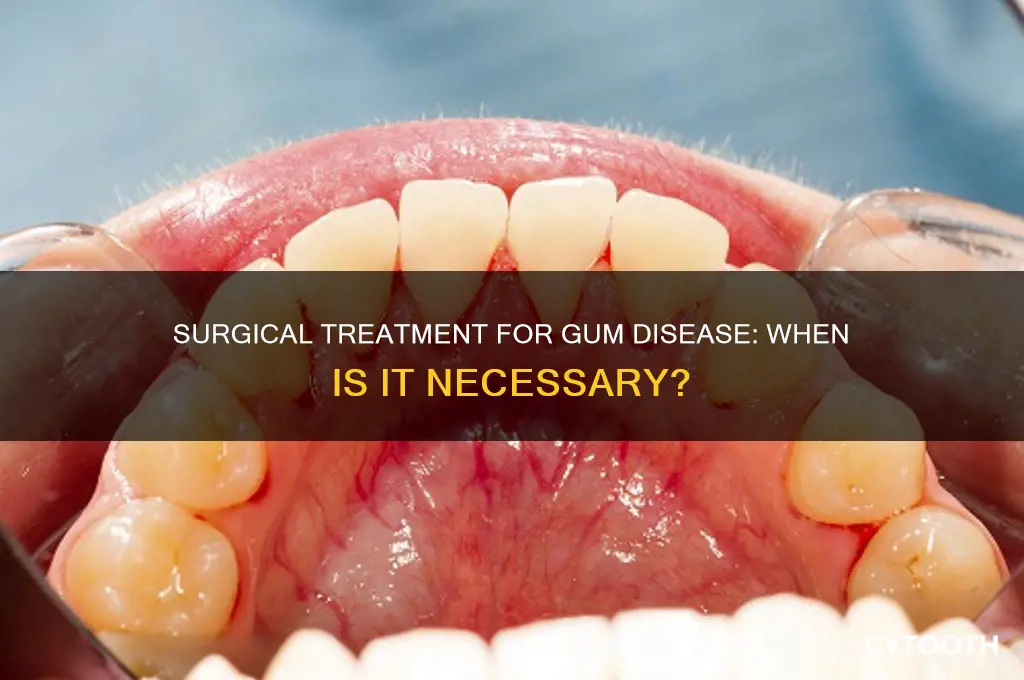

Advanced Periodontitis Stages

Advanced periodontitis represents the most severe stage of gum disease, where the destruction of bone and soft tissue has led to significant tooth mobility and potential tooth loss. At this stage, non-surgical treatments like scaling and root planing are often insufficient to address the extent of damage. Surgical intervention becomes necessary to halt disease progression, regenerate lost tissue, and preserve oral function. The decision to proceed with surgery is typically based on the depth of periodontal pockets, the degree of bone loss, and the patient’s overall oral health. Without timely intervention, advanced periodontitis can result in irreversible damage, impacting not only oral health but also systemic well-being.

One of the primary surgical approaches for advanced periodontitis is flap surgery, also known as pocket reduction surgery. During this procedure, the periodontist lifts back the gums to remove tartar and bacteria from deep pockets, then sutures the gums snugly around the tooth to reduce pocket depth. In cases where bone loss has occurred, bone grafting may be performed to regenerate lost bone tissue. This involves placing natural or synthetic bone material into the affected area to stimulate new bone growth. While flap surgery is highly effective, it requires meticulous post-operative care, including regular follow-ups and excellent oral hygiene, to ensure long-term success.

Another surgical option for advanced periodontitis is guided tissue regeneration (GTR), a technique used when the bone supporting the teeth has been destroyed. GTR involves inserting a biocompatible membrane between the gum tissue and the tooth to prevent unwanted tissue growth into the healing area, allowing bone and connective tissue to regenerate. This procedure is particularly beneficial for patients with deep bone defects. However, GTR is more complex and requires a skilled periodontist to perform. Patients should be aware that recovery may take several weeks, during which discomfort and swelling are common.

Soft tissue grafts may also be necessary in advanced periodontitis cases where gum recession has exposed tooth roots, leading to sensitivity and increased risk of decay. Tissue is typically taken from the palate or a donor source and sutured to the affected area to reinforce the gums. This procedure not only improves aesthetics but also helps reduce pocket depth and protect vulnerable root surfaces. Patients undergoing soft tissue grafts should avoid smoking and follow a soft diet for at least a week post-surgery to ensure proper healing.

Ultimately, the decision to pursue surgical treatment for advanced periodontitis hinges on the severity of the condition and the patient’s commitment to post-operative care. While surgery can be invasive and require a significant recovery period, it offers the best chance to save teeth, restore oral health, and prevent further complications. Patients must work closely with their periodontist to develop a comprehensive treatment plan, including regular maintenance therapy, to prevent disease recurrence. Ignoring advanced periodontitis or delaying surgical intervention can lead to tooth loss and contribute to systemic health issues, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Early detection and proactive treatment remain the most effective strategies for managing this debilitating condition.

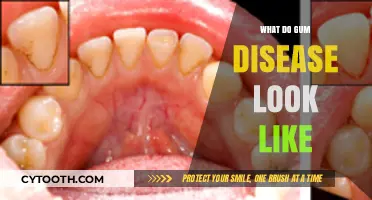

Recognizing Gum Disease: Symptoms, Appearance, and Early Warning Signs

You may want to see also

Severe Bone Loss Cases

Severe bone loss in gum disease, or periodontitis, marks a critical stage where non-surgical treatments fall short. At this point, the disease has eroded the alveolar bone supporting the teeth, leading to mobility, tooth migration, or even tooth loss. Surgical intervention becomes necessary to halt progression, regenerate lost tissue, and restore oral function. Without timely action, the damage becomes irreversible, compromising not only oral health but also systemic well-being.

Consider the case of a 45-year-old patient with advanced periodontitis, whose X-rays reveal 50-70% bone loss around multiple molars. Non-surgical scaling and root planing have failed to control infection, and pocket depths exceed 7mm. Here, surgical treatment, such as flap surgery or bone grafting, is essential. Flap surgery involves lifting the gums to remove tartar and reshape the bone, while bone grafting uses synthetic or natural materials to regenerate lost bone. Post-surgery, the patient must adhere to rigorous oral hygiene and regular maintenance visits to prevent recurrence.

Analyzing the decision-making process, surgeons evaluate several factors before recommending surgery. These include the extent of bone loss, the patient’s overall health, and their ability to comply with post-operative care. For instance, smokers are at higher risk of surgical failure due to impaired healing, making smoking cessation a prerequisite. Additionally, patients with diabetes or immunocompromised conditions may require tailored treatment plans to ensure optimal outcomes.

From a comparative perspective, surgical treatments for severe bone loss offer distinct advantages over non-surgical methods. While scaling and root planing can manage mild to moderate cases, they cannot address deep pockets or regenerate bone. Surgical options, such as guided tissue regeneration (GTR) or enamel matrix derivative (EMD) application, provide a more targeted approach. GTR uses a barrier membrane to promote bone regrowth, while EMD stimulates natural tissue repair. These techniques, though more invasive, yield better long-term results in severe cases.

Practically, patients undergoing surgical treatment for severe bone loss must follow specific post-operative instructions to ensure success. This includes avoiding hard or crunchy foods for 4-6 weeks, using prescribed antimicrobial mouthwash, and taking pain medication as needed. Swelling and discomfort are common for the first few days, but ice packs and elevation can alleviate symptoms. Regular follow-ups are crucial to monitor healing and address any complications promptly. By combining surgical expertise with patient diligence, severe bone loss cases can be managed effectively, preserving oral health and quality of life.

Understanding Gum Disease Progression: How Quickly Can It Advance?

You may want to see also

Persistent Gum Infections

Consider the case of a 45-year-old patient with persistent gum infections despite biannual cleanings and meticulous oral hygiene. Radiographs reveal significant alveolar bone loss, and probing depths exceed 7 millimeters in multiple sites. Here, flap surgery, also known as pocket reduction surgery, is recommended. This procedure involves lifting back the gums to remove tartar and bacteria, then suturing the gums snugly around the tooth to reduce pocket depth. Post-surgery, the patient must adhere to a regimen of chlorhexidine mouthwash (0.12% concentration, twice daily for two weeks) and avoid smoking, as tobacco use impairs healing and increases infection risk.

Comparatively, regenerative procedures like bone grafting or guided tissue regeneration (GTR) may be employed when persistent infections have caused substantial bone destruction. These techniques aim to restore lost bone and tissue, using materials like bioactive glass or membrane barriers to stimulate regrowth. For example, a 50-year-old diabetic patient with advanced periodontitis might benefit from GTR, as diabetes exacerbates gum disease and complicates healing. However, such procedures require strict post-operative care, including a soft diet for 4–6 weeks and frequent follow-ups to monitor tissue integration.

Persuasively, surgical treatment for persistent gum infections is not merely a last resort but a proactive measure to prevent systemic health complications. Research links untreated periodontitis to conditions like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and respiratory infections. For instance, oral bacteria can enter the bloodstream, triggering inflammation in distant organs. Thus, addressing persistent infections surgically not only preserves oral function but also mitigates broader health risks. Patients must weigh the temporary discomfort of surgery against the long-term benefits of infection control and systemic well-being.

Instructively, recognizing early signs of persistent gum infections can expedite the need for surgical intervention. Symptoms such as chronic bad breath, gum recession, or pus discharge warrant immediate dental evaluation. Patients should maintain a log of symptoms and share it with their periodontist to facilitate timely diagnosis. Additionally, incorporating interdental brushes and antimicrobial rinses into daily routines can complement surgical outcomes, ensuring sustained periodontal health post-treatment. By combining surgical precision with proactive self-care, patients can effectively combat persistent gum infections and safeguard their oral and systemic health.

Effective Home Remedies to Treat Gum Disease Without Dental Visits

You may want to see also

Failed Non-Surgical Therapy

Surgical intervention for gum disease becomes necessary when non-surgical treatments fail to halt disease progression or restore oral health. This failure often manifests as persistent inflammation, deepening periodontal pockets, or continued bone loss despite rigorous non-surgical efforts. Understanding why and how non-surgical therapy fails is critical for determining the appropriate next steps in patient care.

Analyzing Failure Points in Non-Surgical Therapy

Non-surgical treatments, such as scaling and root planing (SRP), antimicrobial therapy, and improved oral hygiene, are typically the first line of defense against gum disease. However, failure can occur due to several factors. Poor patient compliance with at-home care, such as inadequate brushing or flossing, undermines treatment efficacy. Additionally, certain systemic conditions, like uncontrolled diabetes or smoking, can impair healing and exacerbate disease activity. Even when patients adhere to recommendations, anatomical complexities—such as deep pockets or furcations—may prevent thorough mechanical debridement, allowing bacterial biofilm to persist.

Clinical Indicators of Treatment Failure

Clinicians must monitor specific indicators to assess the success of non-surgical therapy. Persistent probing depths greater than 5–6 mm, bleeding on probing, and radiographic evidence of ongoing bone loss are red flags. For instance, if a patient undergoes SRP and, after 3–4 months of reevaluation, still exhibits these signs, it suggests that non-surgical measures are insufficient. Similarly, recurrent periodontal abscesses or worsening mobility of teeth indicate uncontrolled infection, necessitating a reevaluation of treatment strategies.

Persuasive Case for Surgical Intervention

When non-surgical therapy fails, surgical treatment becomes not just an option but a necessity to prevent irreversible damage. Surgical procedures, such as flap surgery or bone grafting, provide access to areas that non-surgical methods cannot reach, enabling more comprehensive removal of diseased tissue and regeneration of lost bone. For example, a patient with persistent pockets in the molar region despite SRP may benefit from flap surgery to eliminate subgingival calculus and smooth root surfaces, reducing pocket depth and promoting healing. Delaying surgical intervention in such cases risks further bone loss and potential tooth loss.

Practical Steps for Transitioning to Surgery

Transitioning to surgical treatment requires a systematic approach. First, reevaluate the patient’s oral hygiene practices and systemic health to address modifiable risk factors. If compliance is optimal and systemic conditions are managed, proceed with surgical planning. Pre-surgical steps include obtaining updated radiographs and discussing the procedure, risks, and benefits with the patient. Post-surgery, emphasize the importance of maintenance therapy, including regular periodontal cleanings every 3–4 months, to ensure long-term success. For instance, a 45-year-old patient with failed SRP due to deep pockets around the molars might undergo flap surgery followed by a strict maintenance regimen to prevent recurrence.

Comparative Outcomes: Surgery vs. Continued Non-Surgical Care

Studies show that surgical intervention yields superior outcomes in cases of advanced periodontitis compared to continued non-surgical care. For example, a 2019 systematic review published in the *Journal of Clinical Periodontology* found that surgical therapy resulted in significantly greater pocket reduction and clinical attachment gain compared to non-surgical treatment alone in patients with refractory disease. While surgery may seem invasive, it offers a more definitive solution by addressing the root cause of persistent infection, ultimately preserving tooth structure and function. In contrast, prolonging non-surgical therapy in failing cases may lead to unnecessary disease progression and increased treatment complexity.

In summary, failed non-surgical therapy serves as a clear signal for surgical intervention in gum disease management. By recognizing failure points, monitoring clinical indicators, and understanding the comparative benefits of surgery, clinicians can make informed decisions to optimize patient outcomes and prevent further oral health deterioration.

Can Gum Disease Be Cured? Understanding Treatment and Prevention Options

You may want to see also

Deep Pocket Reduction Needs

Surgical intervention for gum disease becomes necessary when non-surgical treatments fail to control the progression of periodontitis. One critical procedure in this context is deep pocket reduction, aimed at eliminating bacterial reservoirs and facilitating gum reattachment to the tooth surface. This intervention is typically considered when periodontal pockets exceed 5 millimeters in depth, as measured during a comprehensive periodontal evaluation. Such deep pockets harbor harmful bacteria that contribute to bone and tissue destruction, making them a primary target for surgical correction.

The process of deep pocket reduction involves flap surgery, where the gums are lifted back to expose the roots for thorough cleaning. Scaling and root planing are performed to remove plaque, tartar, and bacterial toxins, smoothing the root surfaces to discourage further bacterial accumulation. Once cleaned, the gums are sutured tightly around the tooth to reduce pocket depth, minimizing spaces where bacteria can thrive. Post-operative care is crucial, often involving antimicrobial mouth rinses, such as 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate, prescribed for 2–4 weeks to control infection and promote healing.

While deep pocket reduction is effective, it is not without risks. Potential complications include increased tooth sensitivity, gum recession, and, in rare cases, infection. Patients must adhere strictly to post-surgical instructions, including avoiding smoking, as it impairs healing and increases the risk of treatment failure. Regular follow-up appointments are essential to monitor healing and perform maintenance therapy, such as periodontal cleanings every 3–4 months, to prevent disease recurrence.

Comparatively, non-surgical treatments like scaling and root planing are less invasive but may be insufficient for advanced cases. Deep pocket reduction offers a more definitive solution by physically altering the periodontal environment, making it less hospitable to pathogenic bacteria. However, it requires a higher level of patient commitment to oral hygiene and maintenance care. For individuals with systemic conditions like diabetes or immunocompromised states, surgical intervention may be particularly critical, as these conditions can exacerbate gum disease progression.

In conclusion, deep pocket reduction is a vital surgical option for managing advanced gum disease, particularly when pocket depths exceed 5 millimeters. Its success hinges on meticulous cleaning, precise surgical technique, and rigorous post-operative care. While it carries risks, the procedure offers a transformative solution for halting disease progression and preserving oral health, making it an indispensable tool in periodontal therapy.

Recognizing Early Signs of Periodontal Disease: Symptoms and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Surgical treatment is typically required for advanced stages of gum disease, such as periodontitis, when non-surgical methods like scaling and root planing fail to control the infection or when there is significant bone or tissue damage.

Common surgical procedures include flap surgery (pocket reduction surgery), bone grafting, soft tissue grafts, and guided tissue regeneration. The choice of procedure depends on the severity and location of the damage.

Your dentist or periodontist will evaluate your condition through a comprehensive exam, including X-rays and measurements of gum pockets. If deep pockets, bone loss, or persistent infection are detected, surgical intervention may be recommended.

Recovery varies depending on the procedure, but generally involves mild discomfort, swelling, and bleeding for a few days. Patients are advised to follow a soft diet, maintain oral hygiene, and attend follow-up appointments to ensure proper healing.