Braces are a common orthodontic treatment used to straighten teeth and correct bite issues by applying consistent, controlled pressure to gradually shift teeth into their desired positions. One of the most fascinating aspects of braces is their ability to rotate a tooth, a process that involves precise manipulation of the forces exerted by brackets, wires, and elastics. By strategically adjusting the tension and angle of the archwire, braces create a rotational force that targets the tooth’s center of resistance, causing it to turn within the alveolar bone. This rotation is achieved without damaging the tooth or its surrounding structures, thanks to the slow and steady application of pressure, which allows the periodontal ligaments and bone to remodel over time. Understanding this mechanism highlights the intricate science behind orthodontic treatments and how braces can achieve complex tooth movements with remarkable precision.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mechanism | Braces apply controlled, continuous force to the tooth, causing it to move in the desired direction. Rotation is achieved by placing brackets and wires strategically to create torque and angulation forces. |

| Force Application | Light, continuous forces (typically 50-200 grams) are applied to avoid root resorption and ensure controlled movement. |

| Bracket Placement | Brackets are positioned off-center on the tooth to create a moment of force, facilitating rotation. |

| Archwire Interaction | The archwire is shaped to apply rotational forces by engaging the bracket slots at specific angles. |

| Biological Process | Pressure on one side of the tooth causes bone resorption (breakdown), while tension on the other side stimulates bone deposition (formation), allowing the tooth to rotate. |

| Duration | Rotation typically takes 3-6 months, depending on the degree of rotation needed and individual response. |

| Monitoring | Regular adjustments (every 4-8 weeks) are made to the archwire and brackets to maintain optimal force levels. |

| Auxiliary Aids | Elastic chains, coils, or temporary anchorage devices (TADs) may be used to enhance rotational control. |

| Patient Compliance | Proper oral hygiene and avoiding hard, sticky foods are crucial to prevent complications and ensure successful rotation. |

| Technology | Modern techniques like self-ligating braces and clear aligners (e.g., Invisalign) can also achieve rotation with improved aesthetics and comfort. |

What You'll Learn

- Biomechanics of Tooth Movement: Forces applied by braces create pressure, stimulating bone remodeling for rotation

- Archwire Role: Shape and material of archwires dictate torque and rotational forces on teeth

- Bracket Placement: Precise bracket positioning ensures controlled rotation during orthodontic treatment

- Bone Remodeling Process: Osteoclasts and osteoblasts reshape bone, allowing tooth rotation under pressure

- Treatment Time Factors: Rotation speed depends on tooth size, root length, and applied force

Biomechanics of Tooth Movement: Forces applied by braces create pressure, stimulating bone remodeling for rotation

The force exerted by braces on teeth is a delicate balance of physics and biology, a symphony of pressure and response. When a bracket and wire system is applied, it creates a controlled force vector, typically measured in grams or ounces, that acts on the tooth's center of resistance. This force must be precisely calibrated—too little, and the tooth won’t move; too much, and it risks damaging the periodontal ligament (PDL) or causing root resorption. For rotation, the force is applied asymmetrically, with higher pressure on one side of the tooth, creating a moment that initiates rotational movement. For example, a 50-gram force applied at a specific angle can effectively rotate a front tooth over several months, while maintaining the health of the surrounding bone and soft tissues.

Bone remodeling is the unsung hero of tooth rotation, a process driven by the body’s natural response to mechanical stress. When braces apply force, the PDL fibers on the tension side (where the tooth is pulled) are stretched, stimulating osteoclasts to resorb bone. Simultaneously, on the compression side (where the tooth is pushed), osteoblasts are activated to form new bone. This dynamic interplay, known as the *Haversian remodeling system*, occurs at a microscopic level, with bone turnover rates increasing by up to 50% in the active zone. Orthodontists often monitor this process through periodic X-rays, ensuring the tooth moves at a rate of approximately 1mm per month without compromising bone density or tooth stability.

The biomechanics of rotation demand precision in both force application and patient compliance. For instance, elastic bands or coil springs may be used to augment rotational forces, but these require consistent wear—typically 20–22 hours per day—to achieve the desired effect. Age plays a critical role here: younger patients (under 18) often experience faster bone remodeling due to higher metabolic activity, while adults may require longer treatment times and more controlled forces to avoid complications. Practical tips include avoiding hard or sticky foods that can disrupt appliance integrity and using orthodontic wax to alleviate discomfort from wires or brackets during the rotation process.

Comparing rotational movement to other orthodontic adjustments highlights its unique challenges. While tipping or extrusion primarily involves single-plane movement, rotation requires control in three dimensions, making it more complex to achieve without unintended side effects. Advanced technologies like clear aligners have attempted to replicate this movement but often fall short in cases requiring precise rotational control, as they rely on sequential, pre-programmed forces rather than continuous, adjustable pressure. Traditional braces, with their customizable wires and auxiliary springs, remain the gold standard for achieving accurate rotation, particularly in cases of severe malalignment or complex tooth morphology.

In conclusion, the biomechanics of tooth rotation via braces is a testament to the interplay between mechanical force and biological response. By understanding the principles of force vectors, bone remodeling, and patient-specific factors, orthodontists can orchestrate precise movements that transform smiles. For patients, recognizing the importance of compliance and the science behind their treatment fosters a partnership that ensures both efficiency and safety in achieving optimal results.

Bear Head Tooth Mushroom Hibernation: Survival Secrets of Hericium Americanum

You may want to see also

Archwire Role: Shape and material of archwires dictate torque and rotational forces on teeth

The archwire is the unsung hero of orthodontic tooth movement, a flexible yet formidable force that orchestrates the intricate dance of teeth into alignment. Its role extends beyond mere guidance; the archwire’s shape and material are precision tools that dictate the torque and rotational forces applied to each tooth. For instance, a rectangular archwire exerts greater control over tooth rotation compared to a round one, as its flat surfaces provide more surface area for bracket interaction, enabling finer adjustments. This design specificity ensures that forces are not just applied but are calibrated to the unique needs of each tooth’s movement.

Material selection further refines the archwire’s influence. Nickel-titanium (NiTi) wires, known for their superelastic properties, deliver gentle, continuous forces ideal for initial alignment and rotation. Their flexibility allows them to engage multiple teeth simultaneously, distributing force evenly to avoid over-rotation. In contrast, stainless steel wires, stiffer and more rigid, are employed in later stages to refine tooth position and stabilize results. Orthodontists often transition from NiTi to stainless steel as treatment progresses, leveraging the material properties to match the evolving demands of tooth movement.

Consider the mechanics of torque control, a critical aspect of tooth rotation. A rectangular archwire with a vertical dimension greater than its horizontal dimension inherently promotes torque by engaging the bracket slot at specific angles. This design forces the tooth crown to tip in the desired direction while the roots follow suit, ensuring controlled three-dimensional movement. For example, a 0.018-inch slot paired with a 0.019 x 0.025-inch archwire creates a precise fit that maximizes rotational and torquing forces without compromising stability.

Practical application requires careful planning. Orthodontists must assess the initial malrotation of each tooth, selecting archwire dimensions and materials that align with treatment goals. For severe rotations, a thicker or more rigid wire may be necessary to overcome resistance, while milder cases benefit from thinner, more flexible options. Patients should be advised that archwire adjustments are gradual, with changes typically made every 4–6 weeks to allow teeth to adapt without undue stress. Regular follow-ups ensure that forces remain optimal, preventing overcorrection or stagnation.

In essence, the archwire’s shape and material are not arbitrary choices but deliberate decisions that shape the outcome of orthodontic treatment. By understanding their mechanics, both practitioners and patients can appreciate the precision behind tooth rotation, transforming what seems like a simple wire into a sophisticated instrument of dental transformation.

Exploring the Unique Bear Head Tooth Mushroom: Identification and Uses

You may want to see also

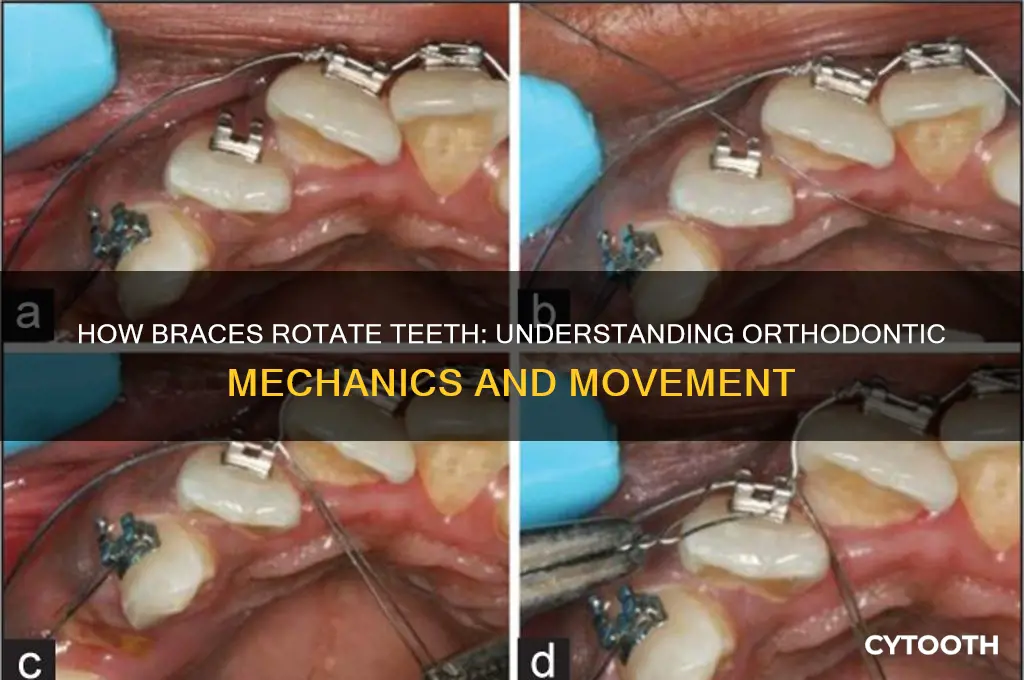

Bracket Placement: Precise bracket positioning ensures controlled rotation during orthodontic treatment

Precise bracket placement is the linchpin of controlled tooth rotation in orthodontic treatment. Each bracket acts as a miniature anchor, strategically positioned to apply targeted forces that guide the tooth’s movement. Even a millimeter of misalignment can alter the torque, tipping, or rotational forces, leading to unintended outcomes. For instance, a bracket placed too far incisally (toward the biting edge) on a front tooth may cause it to tip outward instead of rotating properly. Orthodontists use detailed measurements, often aided by digital tools like cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), to ensure brackets are placed at the tooth’s center of resistance—the point where forces produce pure rotation without unwanted side effects.

Consider the mechanics: brackets are bonded to the tooth surface and connected by an archwire, which exerts pressure to initiate movement. The bracket’s slot and base angle are designed to interact with the archwire in specific ways, dictating the direction and degree of rotation. For example, a bracket with a 0-degree torque prescription is used for neutral positioning, while a bracket with positive or negative torque values helps control the tooth’s angulation in the vertical plane. If a bracket is placed off-center, the archwire’s force may be unevenly distributed, causing the tooth to tip rather than rotate. This precision is particularly critical for anterior teeth, where even slight rotational discrepancies are highly visible.

The process of bracket placement is both an art and a science. Orthodontists often use indirect bonding techniques, where brackets are pre-positioned on a model of the patient’s teeth and transferred to the mouth using a custom tray. This method allows for meticulous planning and reduces the risk of errors during direct bonding. For younger patients (ages 10–14), whose teeth are still developing, precise bracket placement is even more crucial, as their periodontal ligaments are more responsive to forces, making movement faster but also more sensitive to mistakes. Adults, on the other hand, may require longer treatment times due to less pliable bone structure, making accuracy in bracket placement non-negotiable to avoid prolonged treatment.

A practical tip for patients: maintain excellent oral hygiene around brackets to prevent decalcification or white spots, which can occur if plaque accumulates near the bracket margins. Use a proxabrush or interdental cleaner to navigate around the bracket and wire. Additionally, avoid hard or sticky foods that could dislodge a bracket, as even a minor shift can disrupt the carefully planned rotational forces. Regular adjustments every 4–6 weeks are essential to monitor progress and ensure the archwire continues to apply the correct pressure.

In conclusion, precise bracket placement is not just a technical detail—it’s the foundation of successful tooth rotation in orthodontic treatment. By aligning brackets with the tooth’s center of resistance and using tailored prescriptions, orthodontists can predictably control movement, ensuring aesthetic and functional outcomes. Patients who understand this process can better appreciate the importance of compliance and maintenance, contributing to a smoother treatment journey.

How Braces Gently Pull Teeth Forward: The Orthodontic Process Explained

You may want to see also

Bone Remodeling Process: Osteoclasts and osteoblasts reshape bone, allowing tooth rotation under pressure

The subtle yet powerful dance of osteoclasts and osteoblasts lies at the heart of how braces rotate teeth. These specialized cells are the architects of bone remodeling, a process that allows teeth to shift under the controlled pressure exerted by orthodontic appliances. Osteoclasts, the bone-resorbing cells, break down bone tissue on the side of the tooth where pressure is applied, creating space for movement. Simultaneously, osteoblasts, the bone-forming cells, rebuild bone on the opposite side, anchoring the tooth in its new position. This dynamic interplay ensures that tooth rotation is not just a mechanical process but a biological one, rooted in the body’s natural ability to adapt and reshape itself.

Consider the mechanics of this process: when braces apply force to a tooth, the periodontal ligament (PDL) surrounding the tooth root experiences tension on one side and compression on the other. This mechanical stress signals osteoclasts to activate on the compressed side, dissolving bone through the release of enzymes and acids. As the tooth begins to move, osteoblasts respond to the tension on the opposite side by depositing new bone matrix, gradually mineralizing it into solid bone. This cycle repeats incrementally, typically at a rate of about 1 mm of tooth movement per month, depending on factors like age, bone density, and the force applied. For adolescents, whose bones are still developing, this process is faster compared to adults, whose bone remodeling is slower due to reduced cellular activity.

To optimize this bone remodeling process, orthodontists carefully calibrate the force applied by braces. Excessive force can overwhelm osteoclasts, leading to root resorption or bone loss, while insufficient force may stall movement altogether. The ideal force range for tooth rotation is typically between 50 to 200 grams, though this varies based on individual factors. Patients can support this process by maintaining good oral hygiene, as inflammation from gum disease can disrupt osteoblast activity. Additionally, a diet rich in calcium, vitamin D, and phosphorus provides the building blocks for osteoblasts to form new bone effectively.

A comparative analysis highlights the elegance of this system: unlike artificial materials, bone remodeling is a self-regulating process that adapts to the needs of the tooth. For instance, if pressure is removed prematurely, osteoblasts and osteoclasts work to stabilize the tooth in its current position, preventing relapse. This contrasts with non-biological systems, which lack such adaptive feedback. Understanding this process underscores the importance of patience and compliance during orthodontic treatment, as the body’s natural mechanisms require time to achieve lasting results.

In practical terms, patients undergoing orthodontic treatment can monitor their progress by observing subtle changes in tooth alignment over weeks or months. While the process may seem slow, each small adjustment reflects the intricate work of osteoclasts and osteoblasts reshaping the alveolar bone. For those concerned about discomfort, over-the-counter pain relievers like ibuprofen (200–400 mg every 6 hours) can alleviate pressure-related soreness. Ultimately, the bone remodeling process is a testament to the body’s remarkable ability to transform under controlled stress, turning orthodontic pressure into precise, permanent tooth rotation.

Treatment Time Factors: Rotation speed depends on tooth size, root length, and applied force

The speed at which braces rotate a tooth is not a one-size-fits-all scenario. It's a delicate dance influenced by three key players: tooth size, root length, and the force applied by the braces. Imagine trying to turn a small, shallowly rooted seedling versus a large, deeply rooted tree—the effort and time required are vastly different. Similarly, smaller teeth with shorter roots respond more quickly to rotational forces than their larger, longer-rooted counterparts. This biological variability means that treatment times can range from a few months to over a year, depending on these factors.

Tooth size plays a pivotal role in rotation speed. Smaller teeth, such as incisors, have less surface area to resist the torque applied by braces, allowing them to rotate more rapidly. In contrast, larger teeth like molars require more force and time to achieve the same degree of rotation. For instance, rotating a lateral incisor might take 3-6 months, while a first molar could take 6-12 months or longer. Orthodontists often use this principle to prioritize treatment, addressing smaller teeth first to expedite overall progress.

Root length is another critical determinant. Teeth with shorter roots experience less resistance during rotation because there’s less surface area anchored in the bone. This makes them more responsive to applied forces. Conversely, teeth with longer roots, such as canines, are more stable and require sustained, carefully calibrated force to rotate effectively. Patients with longer-rooted teeth may need additional tools like temporary anchorage devices (TADs) to enhance control and reduce treatment time.

The force applied by braces is the final piece of the puzzle. Too little force, and rotation stalls; too much, and it risks damaging the tooth’s root or surrounding bone. Orthodontists typically apply forces ranging from 20 to 80 grams per tooth, depending on the tooth type and patient’s bone density. For example, a light force of 20-30 grams might be used for smaller teeth, while a higher force of 50-80 grams could be necessary for larger teeth. Regular adjustments every 4-6 weeks ensure the force remains optimal, balancing speed and safety.

Understanding these factors empowers patients to set realistic expectations and cooperate effectively with their treatment plan. For instance, a patient with smaller, shorter-rooted teeth might see rapid progress, while someone with larger, longer-rooted teeth should prepare for a longer journey. Practical tips include maintaining excellent oral hygiene to prevent complications that could delay treatment and following the orthodontist’s instructions on wearing elastics or other appliances. By recognizing the interplay of tooth size, root length, and applied force, both patients and practitioners can navigate the rotation process with precision and patience.

Frequently asked questions

Braces rotate a tooth by applying consistent, controlled pressure using brackets, wires, and sometimes elastic ties. The archwire is shaped to guide the tooth into the desired position, and as the wire is tightened over time, it exerts force on the bracket, causing the tooth to rotate gradually.

Rotating a tooth with braces can cause mild discomfort, especially after adjustments. This is because the pressure applied to the tooth stimulates the periodontal ligaments and bone, which can feel sore. Over-the-counter pain relievers and orthodontic wax can help alleviate discomfort.

The time it takes to rotate a tooth with braces varies depending on the severity of the rotation and the tooth's position. Generally, it can take anywhere from a few weeks to several months. Complex rotations may require additional tools like power chains or temporary anchorage devices (TADs).

Most teeth can be rotated with braces, but there are limitations. Factors like the tooth's root shape, bone density, and overall oral health play a role. In some cases, severely rotated or misaligned teeth may require additional treatments, such as extractions or surgical intervention, to achieve the desired result.